Antepartum Depression and Resilience: Beyond Symptom Reduction in Pregnancy

Resilience research sheds new light on how we approach antepartum depression, beyond just symptom reduction. Here’s a look at what’s emerging and why it matters for clinical practice.

Content note from Sophia: This article discusses antepartum depression and its potential effects on mothers and children. While the discussion is research-focused, some readers may find the topic sensitive. We also recognise that people who do not identify as women also experience pregnancy. In this article, we use the term “pregnant women” because the current body of research is largely focused on women, but this language is not meant to exclude anyone.

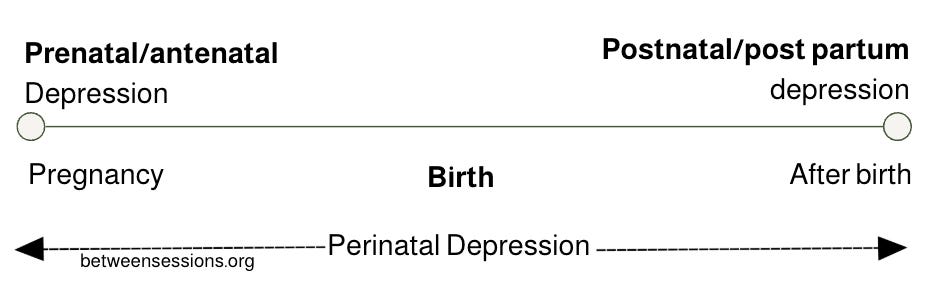

Pregnancy and the transition to motherhood represent profound and life-altering experiences. These phases are accompanied by a complex interaction of physical, emotional, and psychological changes that can significantly impact a woman’s mental health. Among the most prevalent challenges is antepartum depression (ADS), which affects up to 20% of pregnant women during pregnancy.

ADS can severely impair a mother’s social and physical functioning, increase stress, and lower quality of life (Abbaszadeh et al., 2013). Importantly, the effects can extend beyond the mother, maternal depression during pregnancy is associated (not always) with complications in gestation, negative maternal health outcomes, and long-term cognitive, emotional, and behavioural difficulties in children exposed to depression in utero (Gentile, 2017).

Given the high prevalence and far-reaching implications of ADS, early and effective intervention is vital, not only to support maternal well-being but also to promote healthy developmental outcomes for the child.

NOTE: Research on antepartum depression often highlights risks for both mother and child. These findings, and our reporting on this, are not intended nor meant to stigmatise or blame pregnant women. Rather, they underscore the urgent need for early recognition, followed by accessible compassionate, care and social support.

Traditional Treatments and Their Limitations

Research has shown that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) are effective in reducing depressive symptoms in pregnant women. For example, van Ravesteyn et al. (2017) and Claridge (2013) demonstrated that these psychological interventions significantly improved symptom outcomes in women diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) during pregnancy.

However, despite their clinical effectiveness, as you may have found yourself, these traditional treatments are often met with low adherence and high dropout rates. The structured and time-intensive nature of CBT and IPT may not be feasible for many expectant mothers, particularly those facing social or logistical barriers. Additionally, exposure-based CBT has been criticised for potentially increasing physiological stress responses in anxious pregnant women, due to its confrontational nature.

These limitations highlight the need for alternative or complementary approaches, particularly those that enhance engagement and promote positive mental health, rather than focusing solely on symptom reduction.

For CBT practitioners, these findings raise important clinical questions. How might pregnancy affect engagement during therapy? Are standard CBT protocols sufficient for pregnant clients facing depression? What can we do to improve the effectiveness of treatment for these individuals?

Understanding Psychological Resilience

Resilience, as defined by Newman (2022), is “the ability to adapt in the face of trauma, adversity, tragedy, or even significant ongoing stressors.” It is a dynamic process that involves emotional strength, cognitive flexibility, and behavioural adaptability.

Tobe et al. (2020) found low levels of resilience have been associated with increased vulnerability to both antepartum and postpartum depression. This correlation suggests that bolstering resilience during pregnancy may serve as a protective factor against the onset or worsening of depressive symptoms.

Emerging Therapies: ACT, Mindfulness, and the Third Wave

Third-generation behavioural therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) emphasise resilience-building strategies to improve mental well-being. These approaches focus on enhancing psychological flexibility, promoting acceptance, and encouraging present-moment awareness.

A systematic review by Walker et al. (2022) evaluated 10 studies involving pregnant women over the age of 18 with depressive symptoms. Six studies examined the effectiveness of CBT for ADS; five of these found reductions in depressive symptoms.

Notably, all four studies exploring mindfulness-based interventions reported significant improvements compared to control conditions.

These findings are consistent with prior research. For instance, Sockol (2015) found that CBT led to significant reductions in depressive symptoms compared to control groups. Furthermore, postpartum interventions appeared more effective than antenatal interventions, and individualised treatment yielded better outcomes than group treatment, particularly among women who were non-white, single mothers with more than one child.

The Role of Resilience in Depression Prevention

Resilience Training as an Intervention

Resilience-based interventions are gaining attention as a promising component of ADS treatment. Joyce et al. (2018) observed that programs combining CBT and mindfulness practices positively influenced resilience levels. Similarly, Tobe et al. (2020) found that resilience mediated the relationship between anger during pregnancy and postnatal depression. These findings suggest a meaningful clinical application: by identifying individuals with high emotional distress (such as anger) and targeting them with resilience-building interventions, it may be possible to mitigate the risk of developing postnatal depression.

Practical Pathways to Enhancing Resilience and Clinical Implications

So, what does this mean for your clinical work?

According to Waugh and Koster (2015), there are several strategies to cultivate resilience in individuals experiencing depression:

Improving Recovery from Minor Daily Stressors: enhancing stress recovery from everyday challenges can increase overall adaptability and reduce sensitivity to more severe stressors

Promoting Positive Emotions During Stress: encouraging the experience of positive emotion, even in stressful situations, can buffer the emotional impact of adversity

Training Psychological Flexibility: teaching individuals to identify situational demands and apply the most effective coping strategies supports long-term emotional regulation and adaptation

These resilience-focused strategies offer a more empowering, sustainable framework for mental health interventions, particularly during the sensitive perinatal period.

Conclusion: A Resilient Approach to Maternal Mental Health

Antepartum depression is a significant and multifaceted public health issue that affects not only pregnant women, but can also impact the wellbeing of their children. While traditional therapies like CBT and IPT remain valuable, their limitations highlight the need for more adaptive, accessible, and engaging approaches.

Resilience-based interventions, particularly those that incorporate mindfulness, acceptance, and psychological flexibility show more positive and long-term outcomes. By strengthening inner resources rather than solely focusing on symptom management, these approaches empower women to navigate the profound transitions of pregnancy and motherhood with greater emotional strength and adaptability.

Moving forward, clinical practice and research should continue to prioritise early identification of at-risk individuals, while developing and delivering interventions that foster resilience as a core component of maternal mental health.

We also note that much of the existing research has focused on reducing symptoms in the pregnant woman herself. While this is vital, there remains a large research gap in understanding how partners and broader support systems can play a role in treatment and resilience-building. Expanding research in this area could help shift the burden away from the individual and toward more collective, supportive approaches to maternal mental health.

Finally, it is important to underscore that associations between antepartum depression and child outcomes do not mean that mothers are at fault and that these outcomes are always guaranteed. They are not. Depression during pregnancy is not a choice. By focusing on resilience and support, we can move away from blame and toward empowering approaches that benefit both mother and child.

We’d love to hear from you:

How do you tailor your work for pregnant clients experiencing depression? Should therapy for these individuals focus more on enhancing psychological resilience and mindfulness practices rather than symptom reduction? Let us know your thoughts below!

Author: Chloe Williams