Does Clark's Panic Model Work for Teenage Panic Disorder?

Panic disorder peaks in adolescence, yet most treatment models were developed for adults—here's what new research tells us about the gap.

Adolescence is a time of intense change—physically, emotionally, and socially. When panic disorder enters the picture, it can disrupt a teen’s school life, relationships, and identity development. For CBT therapists, early recognition is vital: left untreated, adolescent panic disorder predicts long-term anxiety, depression, substance misuse, and school dropout.

Panic disorders usually begin in adolescence, peaking around age 15.5, with a prevalence of 1 to 3% among 11 to 19 year olds.

Although the onset and peak of panic disorder occur during adolescence, most studies on its symptoms have only included adults. Thus, it remains unclear whether adolescent panic disorder presents the same symptom patterns and clinical impact.

This gap in the literature is significant, given that early onset of the disorder is associated with worse outcomes, including long-term anxiety, school disruption, substance abuse, and suicidal behaviour.1

Why does Panic Disorder strike in adolescence?

Cognitive Changes

Adolescence is not only a stage of bodily changes but also the unique period of development of higher-order cognitions. These include abstract thinking, hypothetical (“what if”) thinking, and cause-and-effect (consequential) reasoning.

The changes in the body and in the mind, could mismatch and lead to erroneous interpretation of body sensations. Teens begin experiencing new bodily sensations during puberty including dizziness, shortness of breath or racing heart.2 With their developing ability to think abstractly and reason using “what if” scenarios, an adolescent might interpret a normal increase in heart rate after climbing stairs as a sign of serious medical problem (What if I am having a heart attack?).

Because of their hypothetical reasoning and focus on possible negative consequences, they may start avoiding physical activity or constantly checking their pulse as a safety-seeking behaviour, even though the sensation itself is harmless.

Examples of this process can be observed both in school life and in social contexts; which could be the possible reason why adolescents with panic disorder usually show school non-attendance. Almost every teen has faced the dreaded moment of standing in front of the whole class to give a presentation - a nerve wracking experience that rarely feels fun or easy.

With newly developed hypothetical reasoning skills, a teen who notices their hand shaking and heart pounding in front of the whole class might think: “What if I completely forget what I say? What if they laugh at me? What if I faint in front of everyone?”

The consequential thoughts turn a normal stress response into a feared catastrophe and possible panic attack once the on-set of physical symptoms becomes relentless. As a result, the student might try and avoid presentations, skip school, or read directly from notes to reduce the chance of embarrassment, which are all forms of safety-seeking behaviour.

Neurobiological Changes

The main brain regions that are affected in panic disorder are the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex (PFC), in both adults and adolescents. Amygdala is the centre for emotion processing, mostly associated with fear. It is responsible for fast fear response to perceived threats.3

The other region affected is the PFC, which has different subdivisions, including attention regulation, memory processing, response inhibition and emotion regulation. It helps with cognitive reappraisal and down-regulating fear responses by controlling amygdala activity.4 Adolescents and adults with panic disorder both show decreased connectivity between amygdala and the PFC5. It is also important to note that this is a normal feature of the adolescent brain, even without being diagnosed with the disorder, which shows the increased tendency of adolescents experiencing panic disorder symptoms.

The impact of reduced connectivity between the amygdala and PFC means less top-down regulation of fear; not making sense of what you are feeling.6 Therefore, instead of calming themselves with rational reappraisal, adolescents may be more prone to catastrophic thoughts when they notice bodily sensations (e.g., dizziness, rapid heartbeat), increasing vulnerability to panic symptoms.

Clark’s Model

Clark’s model of panic disorder describes the behavioural and cognitive patterns believed to be central to the development and maintenance of the condition, which are considered specific to panic disorder. A caveat to this model is that it is only applicable to adults, as studies on this model only included participants above the age of 18.

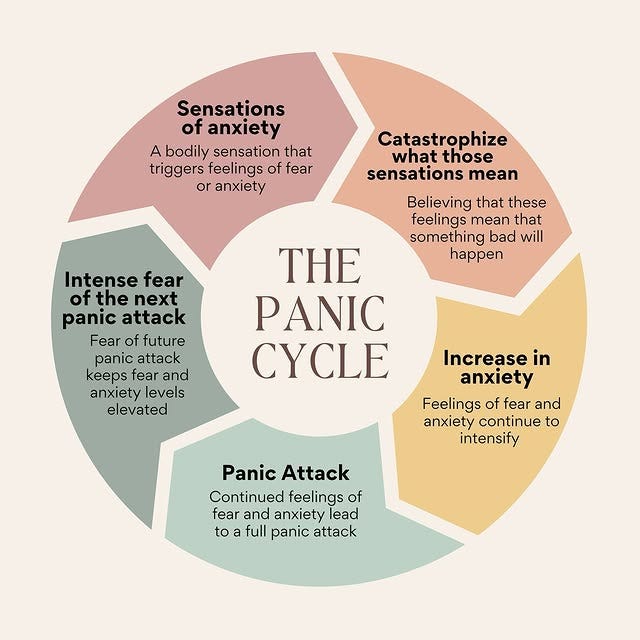

The cognitive model suggests that panic attacks happen due to the misinterpretation of normal body sensations as dangerous, termed a “catastrophic misinterpretation”.

The thought of this misinterpretation and believing that it will lead to a catastrophe, is called having a “catastrophic cognition”.

To give an example, a student giving a class presentation experiencing light-headedness might understand this as a sign that they are going to faint. The “catastrophic cognition” here is the “I’m going to faint”, and the “catastrophic misinterpretation” is the “I feel lightheaded, so I will faint”. This makes the individual hyper-aware of their body sensations and similar sensations will hint that another catastrophe is coming. To avoid this happening, they use safety-seeking behaviours.7 As mentioned earlier, in the context of giving a class presentation, these could be reading directly from notes or avoiding coming to school on presentation days.

Spotting the Red Flags of Panic Disorder in Adolescents

McCall et al. (2025)1 is one of the few studies which focuses on adolescence PD. Their research aimed to describe the clinical characteristics of adolescents with panic disorder. They also compared the symptoms of panic disorder in teens with other anxiety disorders and with healthy controls. The study also aimed to find out whether three components of Clark’s model exist in adolescents with panic disorder: panic (catastrophic) cognitions, fear of body sensations, and safety-seeking behaviours.

Findings

Panic Disorder VS. Anxiety Disorders in Adolescents

Panic Disorder group showed:

Higher overall anxiety severity

More frequent and severe panic symptoms

Higher depressive symptoms

Greater school impairment, including: increased school refusal, more absenteeism

Greater social impairment (difficulty maintaining friendships, avoiding social settings

More emergency healthcare use (likely due to panic attacks being mistaken for physical illness)

Panic Disorder Symptom Severity

The analysis indicated that panic (catastrophic) cognitions, fear of bodily sensation, and safety-seeking behaviours are positively correlated with panic disorder symptom severity. When compared to the anxiety disorders group and healthy group, adolescents with panic disorders showed the highest catastrophic thoughts, greater fear of body sensations and more safety-seeking behaviours.

Implications for CBT

These findings implicate the importance of distinguishing between anxiety disorders and panic disorder in adolescents. In addition, for CBT therapists, the results show that the core principles of Clark’s cognitive model of panic disorder can be adopted for younger clients.

Therapist Takeaways:

Catastrophic cognitions matter in adolescence: Adolescents with panic disorder show more panic-related catastrophic thoughts than peers with or without anxiety.

Safety behaviours maintain symptoms: Avoidance and in-situation coping prevent new learning and keep panic happening.

CBT focus is crucial: Target catastrophic misinterpretations and safety behaviours through behavioural experiments.

Developmental sensitivity: Adapt CBT techniques to be age-appropriate, engaging, and mindful of social/peer contexts.

Spotting and addressing catastrophic thoughts and safety behaviours early can prevent years of disruption and distress. Every school refusal, or avoided presentation, could be a chance to intervene.

What’s your go-to strategy for teen panic? Share your thoughts below!

Author: Alara Kayran, MSc

McCall, A., Waite, F., Percy, R., Turpin, L., Robinson, K., McMahon, J., & Waite, P. (2025). Cognitive and behavioural processes in adolescent panic disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 53(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465825000049

Holmbeck, G. N., Colder, C., Shapera, W., Westhoven, V., Kenealy, L., & Updengrove, A. (2012). Working with adolescents: guides from developmental psychology. In P. C. Kendall (ed), Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures (4th edn, pp. 334–383). Guilford Press.

AbuHasan, Q., Reddy, V., & Siddiqui, W. (2023). Neuroanatomy, amygdala. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved August 18, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537102/

Wang, H.-Y., Zhang, L., Guan, B.-Y., Wang, S.-Y., Zhang, C.-H., Ni, M.-F., Miao, Y.-W., & Zhang, B.-W. (2024). Resting-state cortico-limbic functional connectivity pattern in panic disorder: relationships with emotion regulation strategy use and symptom severity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 169, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.11.007

Xie, S., Zhang, X., Cheng, W., & Yang, Z. (2021). Adolescent anxiety disorders and the developing brain: comparing neuroimaging findings in adolescents and adults. General Psychiatry, 34, e100411. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100411

Ochsner, K. N., Silvers, J. A., & Buhle, J. T. (2012). Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x

Clark, D. M., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2009). Panic Disorder. OxCADAT Resources. https://oxcadatresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Cognitive-Therapy-for-Panic-Disorder_IAPT-Manual.pdf