When Substance Use Meets Common Mental Health Problems: A CBT Therapist’s Case for Inclusion

Substance abuse often acts as an exclusion criteria for CBT, but latest research is suggesting inclusion rather than exclusion. We analyse why, when and how.

Fast Facts: CBT and Substance Use

Over-exclusion is common: 57% of clients excluded from NHS talking therapies were drinking below the NICE threshold of 15 units/day.

CBT works for dual diagnosis: Meta-analyses show moderate to large benefits for anxiety, depression, and substance use when treated together.

Use formulation, not checklists: Assess function and impairment rather than automatically excluding based on substance use alone.

Coordinate care for higher risk: Use shared care with addiction services rather than complete exclusion from therapy.

In the NHS, agency work, and in private practice, it’s not unusual to see referrals that mention something like “a few drinks most nights” alongside anxiety or depression. Often, this seemingly minor detail leads to a quick triage decision: “Refer to alcohol services.” But this kind of automatic exclusion can close the door on effective treatment.

The recent audit by Khodayar and colleagues backs up this concern: in one south London talking therapies service, 57% of clients excluded for alcohol use were drinking below the 15-unit/day NICE threshold. This suggests a systematic pattern of over-exclusion that aligns poorly with both best practice guidelines and the flexible, formulation-based philosophy of CBT.

Substance Use and Mental Health: A Nuanced Picture

How Common Is It?

(Note: In psychological treatment research, an effect size of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large. These values help interpret the strength of therapy effects across studies.)

Globally, anxiety and depression frequently co-occur with substance use. A major meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions found that therapy produced moderate benefits for both anxiety and alcohol use (effect sizes ranged from g = 0.29 to 0.44), and large benefits when depression was also present (g = 0.88) [2].

Another review focusing specifically on CBT showed modest but meaningful improvements for both depression and substance use symptoms (g ≈ 0.25) [3].

While some of these numbers might seem small, they are clinically significant, especially in complex co-morbid presentations where even modest gains represent important progress.

What Do Guidelines Say?

NICE and NHS guidance recommend specialist referral for clients drinking > 15 UK units/day, but not exclusion for moderate or low-risk use [7]. CBT is recognised as effective for both mental health and substance use issues; it typically integrates functional analysis and relapse prevention [9].

What the Audit Really Tells Us

In the Cambridge audit of 5,273 NHS Talking Therapy referrals (Jan–Jul 2018), 678 were declined, with 50 citing substance use. Key findings:

57% consumed below the 15-unit/day threshold [1].

Clinician rationales included fears of poor therapy outcomes, assumptions that substance use was primary, and the belief that these clients belonged in addiction services [1].

Taken together, these findings suggest clinicians may be overgeneralising risk, potentially denying effective therapy to those who could benefit greatly.

Why CBT Works in Co-morbid Cases

Core CBT Principles

CBT helps explore how thoughts, feelings, and behaviours interact, not in isolation, but as part of the person’s lived experience. In co-morbid presentations, substance use often serves a specific function, like numbing overwhelming anxiety or avoiding painful self-beliefs. For example, a client might drink to quiet intrusive thoughts tied to guilt or shame. CBT gives us tools to unpack these patterns and collaboratively build healthier ways to cope, without judgment [9].

Evidence of Efficacy

Meta-analysis: 53 RCTs showed CBT had a small but significant effect (g ≈ 0.15) for alcohol and drug use, with stronger effects when combined with other interventions [4].

Psychosocial comorbidity review: moderate effects for anxiety and substance use, with bigger effects on depression [2].

Depression + substance use: CBT showed durable benefits in depression and substance use outcomes [3].

Integrated approaches (e.g., trans-diagnostic or unified protocols) are promising, with emerging evidence of better retention and symptom change [6].

Related Therapies and Adaptations

Behavioural Activation, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Unified Protocols are gaining traction. A pilot study found that Behavioural Activation delivered alongside substance use treatment improved both mood and use outcomes [5]. Integrated ACT protocols among alcohol and trauma/PTSD clients showed high completion (67%) and symptom improvement [6].

Practical Guidance for Informed Inclusion

Based on the evidence and clinical logic, here’s a refined framework for CBT clinicians:

Routine Screening

Use structured tools like AUDIT‑C, AUDIT‑10, or ASSIST‑Lite to objectively gauge risk [8]. Go beyond consumption: assess functional impairment, health, and motivation.

Formulation‑Driven Decisions

Instead of checklist exclusion, ask:

Is substance use impairing participation?

Does the client want help for it?

Does it serve an avoidance or self-soothing function?

What would a CBT formulation look like?

If substance use is manageable and coherent within a formulation, there's a strong rationale for inclusion.

Shared Care for Higher Risk

For clients showing moderate-to-high risk (e.g., high daily units, polydrug use, comorbid physical health issues), coordinated care with addiction services is warranted. Joint risk assessment, shared goals, and liaison meetings can support safe, effective therapy.

Therapist Competence and Reflection

Clinician belief matters. Regular supervision and training in substance use, shared care, and integration of therapies (e.g., ACT, Unified Protocol) can shift practice away from exclusionary heuristics and toward informed inclusion [6].

Binge Drinking and Health Risks: A Nuanced Consideration

While many clients excluded from therapy were drinking below the NICE threshold, the audit found that some engaged in high-risk patterns like binge drinking, or used substances such as methadone, crack, or chemsex-related drugs, which introduced additional risks; medical, psychological, and social [1].

These were valid grounds for pause and reflect the importance of not equating 'below threshold' with ‘safe’. In such cases, structured risk assessment and a collaborative care approach remain essential.

Acknowledging Data Limitations

It's also worth noting that the audit data came from a single NHS Talking Therapies service in London, with assessments carried out by a mix of clinicians (including Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners and CBT Therapists). This means the findings might not generalise across all services, but they do offer valuable insights into national patterns of decision-making that warrant attention [1].

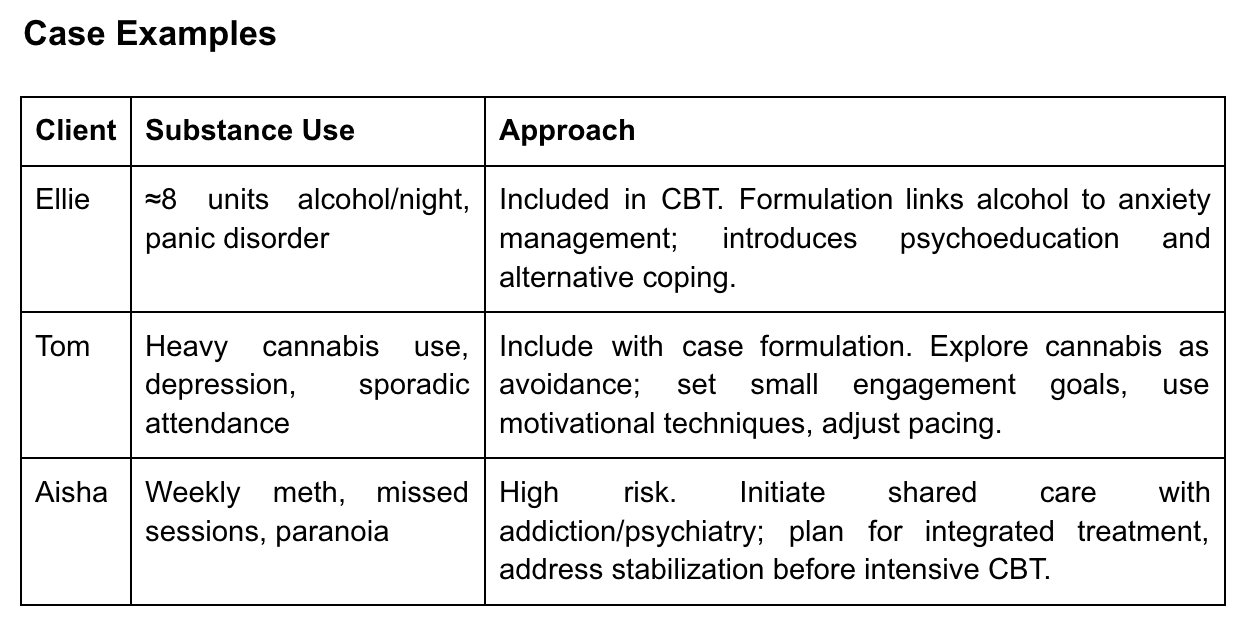

Case Examples

Clinician Reflection Challenge

Think of your own recent case where substance use influenced your decision. Ask:

Did you use a standardised tool?

Were assumptions more influential than data?

Could substance use have become a formulation target rather than a reason to exclude?

What can you do to integrate care in future referrals?

Final Takeaway

The audit findings from Khodayar et al. offer a clear signal: current practice often errs on exclusion, even for low-risk substance users [1]. Yet, the evidence shows CBT is effective and adaptable,even when substance use is present [2–6]. With structured assessment, shared care, and clinician reflection, CBT therapists can confidently offer talking therapies to a broader range of clients,treating the person behind the substance, not just the substance behind the referral.

Share your thoughts: How do you navigate decisions around including clients with substance use in CBT? Share your formulation strategies, tools, or lessons from practice!

Author: Kavya Suresh Kumar

Thank you for this! This really resonates. When I moved from working in drug and alcohol services into IAPT within the same area, it became quickly apparent that there was a lot of confusion and, sadly, a common misconception that substance use automatically meant someone was excluded from therapy. The nuance and context of someone’s coping strategies weren't routinely considered. Fortunately when I brought this up I was tasked with delivering training on the IAPT Positive Practice Guidance across both services, which created more awareness and created an opportunity to open up more conversations. I was ‘allowed’ to develop a care pathway between the two services - one that recognised substance use as part of someone’s broader story, rather than a barrier to receiving support.

That was a few year ago now but I’m always glad to see others increasing awareness of it - these conversations are so important for acknowledging our own fears, misconceptions, areas for development, bias etc and ultimately helping us support people more holistically and effectively.